Ask The Economist: Are Government Agency Banks a Good Idea?

Abir Mandal

People often associate capitalism with “Wall Street greed” and corporate fat cats getting special favors from government. The truth is, anytime the government is involved in the business of anything beyond protecting individual and property rights, it leads to a distortion of the free market and in fact detracts from authentic capitalism. We call this cronyism.

One of the most prominent examples of this phenomenon are government agency banks, such as the World Bank, Export-Import bank (Ex-Im), USAID and the International Monetary Fund. While the stated reasons for such institutions always sound noble, the numbers and perverse incentives they generate tell a different story.

Businesses often turn to such agencies when they are unable to raise enough funds for a project from the private capital markets at an attractive interest rate. The business then approaches the relevant bank to bridge the financing gap—either on the project side (such as to actually construct a factory) or the purchaser side (to finance the purchase of goods and services from the project). Either way, these government banks (and thus taxpayers) assume the risks that private financiers are unwilling to undertake.

Some businesses in the US and abroad claim they need this funding to stay in operation. But this begs the question: if a business cannot exist without being subsidized by the government, wouldn’t the taxpayer dollars being used to prop it up be more efficiently allocated elsewhere by the free market? This would be true capitalism at work and the “creative destruction” that accompanies it. Unfortunately however, many well-connected (and often well-off) shareholders of such businesses continue to benefit from forced taxpayer “generosity.” This hardly seems fair.

Some of these agencies claim to be profitable—i.e. they bring in revenues in excess of what they take from the taxpayers. Even if this were true (and such claims are often doubtful when you account for documented cases of waste and fraud), these claims ignore the “opportunity cost” of the government allocating these funds. (This means we will never know the actual losses from such investments, because the alternative, potential use of this money will never see the light of day.)

For example, when you spend money you have earned, you have incentive to prioritize your spending to ensure that you get the biggest “bang for your buck” possible. You chose carefully, because a bad decision hits you in the wallet where it hurts! But when a government spends taxpayer money, it has no such compulsions since the risk of losses are socialized (ie – borne by you the taxpayer).

And in addition to having little incentive to make good investment decisions, these banks are put in the position of choosing winner and losers among American companies: who will get cheaper, government-guaranteed funds and who will have to play by the regular rules of the game?

Perhaps the most persuasive argument for the US government to back agencies like this is to “level the playing field” for American industries since other countries have similar crony-type institutions. However, if another country is intent on bad fiscal policy (which is what financing otherwise unprofitable ventures entails) this does not mean that the US should do the same.

Instead, the American government should just let its citizens enjoy the cheap products and services made available on the back of taxpayers of other countries and use the dollars saved on true government priorities (such as paying down our enormous debt) or never taking them out of the pockets of taxpayers to start with.

We should do the American people a favor and shut these banks down.

LEARN MORE:

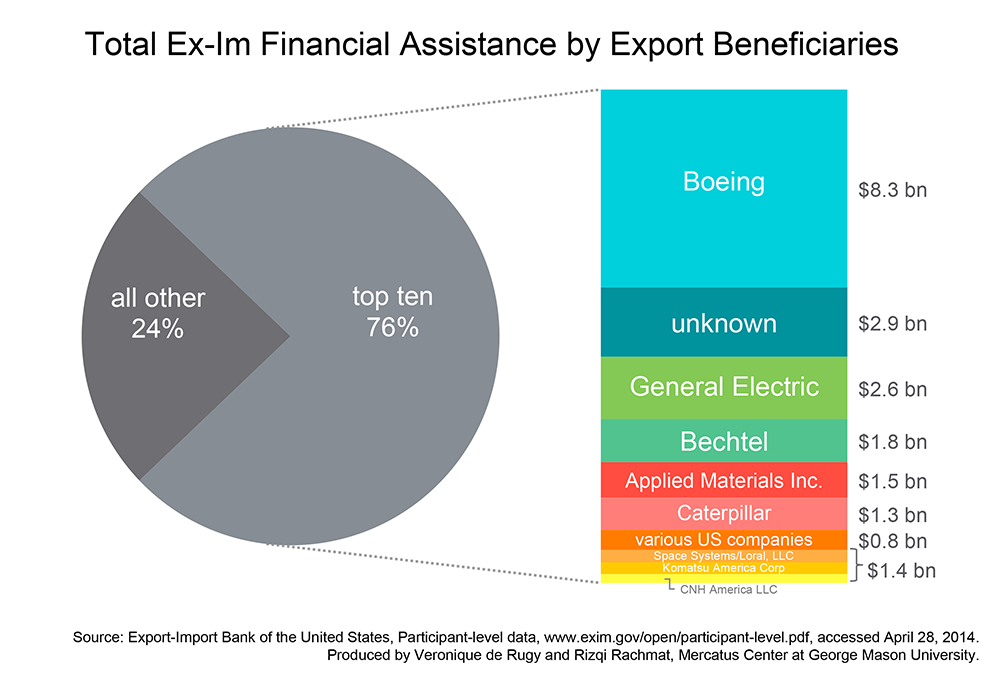

This week, Forum Chairman Jim DeMint writes that only 2 percent of all exports involve Ex-Im assistance. He also shared this helpful chart from the

Mercatus Center at George Mason University showing the breakdown of who benefits from Ex-Im (note the “unknown” section: Ex-Im routinely loses track of whom they’ve been helping.)

—Abir Mandal, PhD Candidate, Clemson University Department of Economics and Palmetto Policy Forum Summer Fellow