How Federal Grants Cause More State Spending

Editor

A new comprehensive study from the Interstate Policy Alliance (IPA) and Palmetto Promise Institute (PPI) concludes that increased federal spending in South Carolina is poor fiscal policy. The study, “Impact of Federal Transfers on State and Local Own-Source Spending,” is authored by Dr. Eric Fruits of Portland State University.

Dr. Fruits’ analysis is part of an ever growing literature that is examining the impact of federal grants on state and local spending, the most significant being the peer-reviewed “Medicaid Expansion, Health Coverage, and Spending: An Update for the 21 States That Have Not Expanded Eligibility,” by Matthew Buettgens, et al. from the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation (2015).

The IPA/PPI research finds significant effects of federal transfers to the states that are associated with increased state and local taxes and charges:

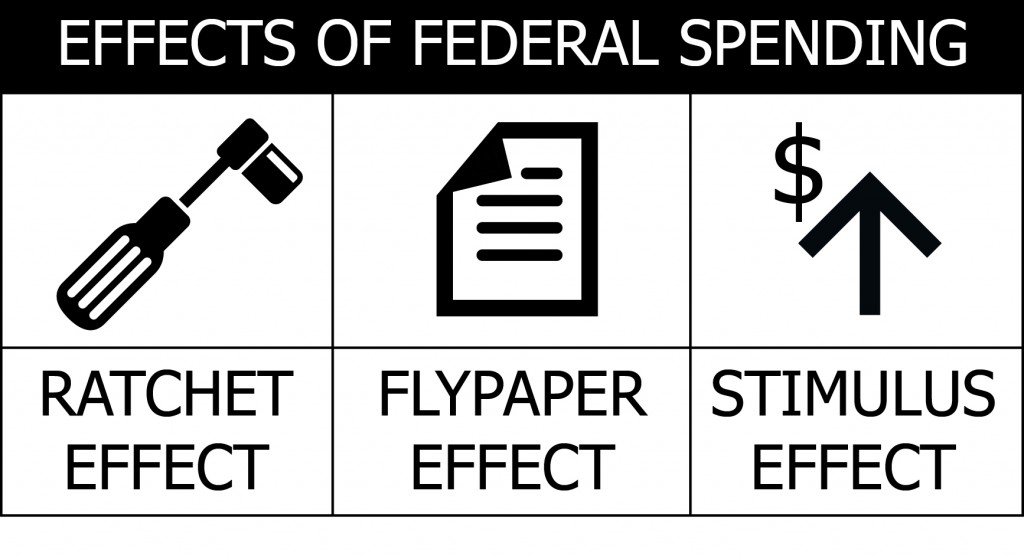

• The “Flypaper” Effect, in which federal funds are accepted as a supplement to, rather than a substitute for state and local taxes and charges.

• The “Stimulus” Effect, in which matching funds and “maintenance of effort” (MOE) requirements tied to federal funds require increased spending from state and/or local funds. In addition, matching requirements may stimulate state and local spending by encouraging projects that are priorities in Washington but not locally, projects that would not have been undertaken without federal funds.

Recent academic research finds that each dollar of additional federal grants to states is associated with a total increase of 54–86 cents in new state and local taxes. The research presented in the IPA/PPI from Portland State supports this finding. IPA/PPI is the most comprehensive analysis to date, using information from U.S. states spanning the period from 1972 to 2012 with controls for state-by-state differences in economic and demographic factors.

IPA/PPI results clearly demonstrate that federal transfers to state and local governments result in a ratcheting up of revenue and taxes. Across states as a group, each dollar of additional federal grants to states is associated with a total increase of 82 cents in new state and local taxes.

The State of South Carolina also has a larger “Ratchet” Effect than states as a group. Statistical analysis, controlling for the economic and demographic factors that vary across states and over time, indicates that—holding other variables constant—each additional $1.00 of federal intergovernmental transfers to South Carolina is associated with a ratcheting of $1.03 in additional taxes, charges, and other state and local source revenue.

In 2012, South Carolina state and local governments received $7.8 billion in federal intergovernmental transfers and spent $28.2 billion raised from state and local sources.

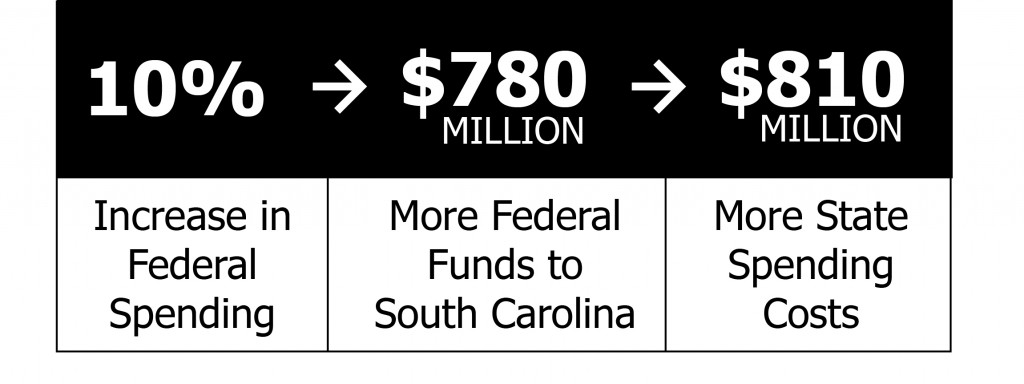

• A hypothetical 10 percent increase in federal transfers to South Carolina would amount to about $780 million more federal money to the state.

• The statistical analysis indicates that this would be associated with approximately $810 million more in spending from state and local sources.

What does this mean for Medicaid expansion?

The Affordable Care Act (ACA), which its authors intended to use to expand Medicaid to nearly all low-income individuals under age 65 with incomes up to 138 percent of federal poverty level, is a classic example of the Stimulus Effect, the Ratcheting Effect, and perhaps the Flypaper Effect as well. Thankfully for the taxpayer, in NFIB v. Sebelius the Supreme Court effectively made the Medicaid expansion optional for each state, and Governor Haley and the General Assembly of South Carolina have opted not to expand Medicaid coverage.

For states that implement the expansion, the federal government will finance 100 percent of the costs of those made newly eligible for Medicaid from 2014 to 2016. Beginning in 2017, the federal contribution is reduced to 95 percent and phases down to 90 percent in 2020 and thereafter. States would continue to pay the traditional Federal Medical Assistance Percentage (FMAP), the Medicaid match rate, for increased participation among those eligible under pre-expansion criteria.

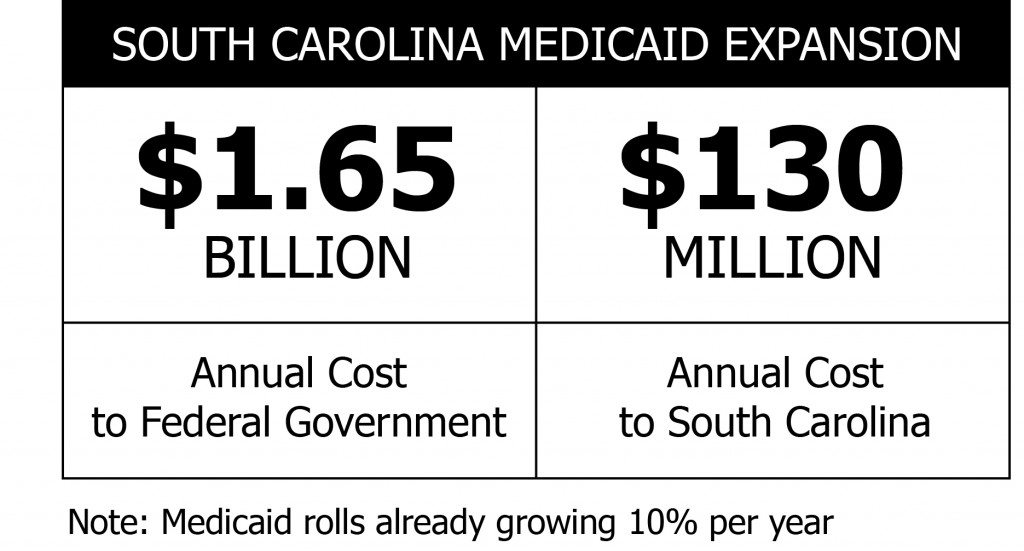

The aforementioned Kaiser Family Foundation, a centrist health care and health insurance think tank, has projected the costs of Medicaid expansion for those states that have not opted to expand. The foundation estimates that the cost the ACA’s Medicaid expansion for South Carolina would be $1.65 billion a year, with the state picking up $130 million a year in additional costs. Those numbers would knock the state budget seriously out of balance, but $130 million could be a meager estimate for at least two reasons.

First, current ACA Expansion states far exceeded estimated costs. For example, Colorado projected growth of 100,000 enrollees but saw their rolls balloon by 307,333. In South Carolina, Medicaid growth—even without ACA Expansion —has been overwhelming for state budget writers. Between July 2013 and August 2015, South Carolina Medicaid enrollment grew by about 91,000. That’s a 10% increase. Medicaid enrollment is now 981,000.

Secondly, according to former US House Ways & Means Chairman and new Speaker Paul Ryan, the likelihood of the federal government maintaining an Expansion population FMAP of 90% for very long after the year 2020 is unlikely. The current Non-Expansion population FMAP of 71.08% could even be in danger.

The South Carolina General Assembly is forbidden from running deficits. Additional Medicaid costs, or any other federal governmental matching requirements must be funded from reductions in spending in other state priorities or an increase in state taxes or fees. As this new IPA/PPI research shows, state policy makers should beware the flypaper, stimulus and ratchet of Uncle Sam in making sound fiscal policy decisions for the Palmetto State.

Sources: