South Carolina’s Direct-to-Consumer Car Sales Bill Ran Out of Time in 2025. Should it be revived in 2026?

As the American automotive industry continues to evolve, several new manufacturers have pursued an alternative go-to-market strategy to the traditional franchised dealer model by creating their own retail operations and selling directly to customers. That list includes Tesla, now one of the world’s biggest automakers, along with growing startups like Rivian and Lucid.

It also includes South Carolina’s own Scout Motors. On March 3, 2023, Scout Motors Inc. announced plans to build a $2 billion vehicle manufacturing plant in Blythewood, South Carolina — the largest economic investment in Richland County’s 240-year history and one of the largest in Palmetto State history. The project is projected to create over 4,000 local jobs and produce a new brand of American-made vehicles, including both fully electric trucks and SUVs and also “Extended Range” versions with built-in gas-powered generators beginning in 2027.

However, without changes to state law, Scout Motors might not be able to sell vehicles directly to South Carolinians in the very state where those vehicles will be made. Scout is just one of the multiple companies blocked from doing business in South Carolina by the state’s regulatory environment when it comes to auto sales.

What the Current Law Says

South Carolina law currently prohibits vehicle manufacturers from selling directly to consumers, requiring all new vehicle sales to be made through franchised dealerships. This traditional model can limit access — particularly for electric vehicles (EVs), which are often sold through direct-to-consumer channels for maximum driver customization. As a result, South Carolinians interested in purchasing EVs like Teslas or Rivians must travel to nearby states such as Georgia, North Carolina, or Virginia, which permit direct sales from at least some new vehicle manufacturers, to complete their purchases. This represents not only an inconvenience for South Carolina car shoppers; it also means that the sales tax revenue will go to other states instead of South Carolina.

This restriction effectively bars automakers that rely exclusively on direct sales from operating in the Palmetto State. Scout Motors plans to adopt a similar direct-sales model and is currently subject to these same legal restrictions, which could prevent hinder the company’s ability to sell vehicles directly to consumers in South Carolina in a convenient way.

A Bill That Could Bring Change

H.3777, known as the Consumer Freedom Act, has a bipartisan group of sponsors including Reps. Mark Smith (R-Berkeley), Craig Gagnon (R-Abbeville), Kambrell Garvin (D-Columbia), and Terry Alexander (D-Florence). This bill would “provide that an automotive manufacturer that owns or operates a manufacturing factory or assembly plant that has never had dealer franchise agreements must be allowed to sell directly to consumers to promote consumer choice and market freedom.”

In other words, H.3777 would amend existing franchise laws to allow automakers with no prior dealer agreements in the last decade to sell vehicles directly to consumers in South Carolina and operate their own service centers without going through third-party dealerships.

Reaction

The ban on direct sales of vehicles to the public has drawn criticism not only from automakers and consumers, but also from advocates of the free market. Conservative supporters of the Consumer Freedom Act argue that allowing manufacturers to sell directly to consumers aligns with the traditional American values of limited government and economic liberty.

- Among the general public, an independent poll found that, out of 500 South Carolinian voters, 83% were unaware of the SC law banning direct sales, and when informed about it, 73% were in support of changing the law.

- Conservative organizations like the Heritage Foundation have long called for the repeal of franchise laws that they view as protectionist, arguing that such laws prevent competition, drive up prices, and limit consumer choice. Heritage contends that in a true free market, manufacturers and buyers should be allowed to interact directly — without government-imposed intermediate ties.

- The Wall Street Journal published an editorial calling for electric vehicles to be freed from the so-called ‘dealer cartel,’ arguing that greater competition and transparency would improve the auto market by increasing consumer confidence in their purchases and ensuring proper deals. The piece criticized Texas’ ban on direct sales and noted that Lucid is prohibited from selling directly to customers in the state. In response, Lucid Group USA filed a lawsuit—Lucid Group USA v. Johnston—challenging Texas laws that require automakers to sell through franchised dealers.

- In a report by our State Policy Network colleagues at Michigan’s Mackinac Center, Dan Crane, who is the Richard W. Pogue Professor at Law at the University of Michigan, called on lawmakers to prioritize consumer benefit and choice over the interests of automakers and car dealerships.

Other analysts argue that traditional dealership laws can prevent innovation in the American automotive industry. In 2015, officials from the Federal Trade Commission issued a statement in support of allowing direct-to-consumer vehicle sales, as Tesla was engaged in a legal battle with the State of Michigan over its right to sell and service vehicles without using franchised dealerships. That case was settled in 2020, resulting in an agreement that permits Tesla to operate service centers and facilitate sales in the state.

Just this March (2025), the U.S. Department of Justice’s Antitrust Division, under the leadership of Trump-appointee Gail Slater, launched the Anticompetitive Regulations Task Force to identify state and federal laws that discourage free market competition. The task force brings together attorneys, economists, and government staff to examine regulatory barriers that may limit innovation, raise costs for consumers, and make it harder for small businesses to compete with larger corporations. Regulations prohibiting direct vehicle sales are one such target of this task force.

Here in South Carolina, Governor Henry McMaster stands in support of changing the SC franchise law. He even said that he would sign the bill for direct EV sales if it came to his desk.

Historical Context of Direct Sales

To understand the controversy of changing franchise law, we must examine the history. The Automobile Dealers Day in Court Act was passed by Congress in 1956, which referred to the automotive industry as entirely consisting of domestic automakers such as Ford, GM, and Chrysler, which at the time were abusing mom and pop businesses that had no bargaining power. The act protects dealers from negligent practices by manufacturers.

In the decades that followed, state legislatures across the country—including in South Carolina—adopted their own franchise laws to further regulate the relationship between manufacturers and dealers. These laws often gave auto dealers more power and protections, solidifying a model in which manufacturers could only sell vehicles through independently owned franchises. Over time, the franchised dealership model became the standard in nearly every state.

However, the legal framework that shaped these laws was based on a market where every major automaker followed the franchise model. It did not foresee the possibility of new companies—especially those founded in the 21st century—that might want to bypass dealerships entirely and sell directly to consumers from the outset, with all the customizable bells and whistles that come with modern vehicles and a more innovative customer experience that aligns with modern consumer preferences.

As a result, manufacturers that never used franchise dealerships have found themselves blocked from entering the market under outdated statutes. For example, in South Carolina, state law currently prohibits not only direct sales of vehicles from manufacturers to consumers but also prohibits those manufacturers from even servicing vehicles within the state.

This restriction stands in contrast to global norms. The U.S. is one of the only countries where such a widespread ban on direct auto sales exists. Even in countries with more highly regulated economies than our free market system, manufacturers are often allowed to sell directly to buyers without involving a government-mandated middleman.

Supporters of changing South Carolina’s law point argue that a direct-to-consumer model can lower vehicle prices by eliminating dealership markups, streamline the buying process, and offer consumers more transparency and convenience. Recent surveys indicate broad public support for these changes, both nationally and within South Carolina.

Some have also raised constitutional concerns about the existing franchise law, arguing that it restricts competition and consumer choice in ways that may violate both state and federal constitutional principles. Although South Carolina’s law was upheld after it was passed in 2000, it has since faced growing scrutiny as the automotive industry evolves. When the legislature asked former Attorney General Charlie Condon to evaluate the law, he said that it was not only unconstitutional but also violates numerous provisions of both the United States and South Carolina Constitutions. This analysis was recently countered by SC Attorney General Alan Wilson, who in February released an opinion interpreting the law in support of franchised dealers.

The Current Legislative Battle

On February 12, 2025, the South Carolina House’s Business and Commerce Subcommittee heard testimony on H.3777.

In that hearing, many supporters argued that the legislation would promote competition, lower car prices, and expand economic freedom for South Carolina consumers.

Zach Han, a senior managing policy advisor at Tesla, testified that it should not be necessary for South Carolinians to leave the state to purchase Teslas and other electric vehicles.

“South Carolina is one of the few remaining states whose laws prevent market competition and block innovative, well-paying jobs from being created locally. Even with that limitation, Tesla has sold more than 13,000 cars to South Carolinians, who have been forced to drive to North Carolina, Georgia, or Tennessee to pick up the car that they wanted,” Han said.

“This is unfair to South Carolinians, and it is quite contradictory to the state’s strong history of supporting the free market, consumer freedom of choice, and innovation.”

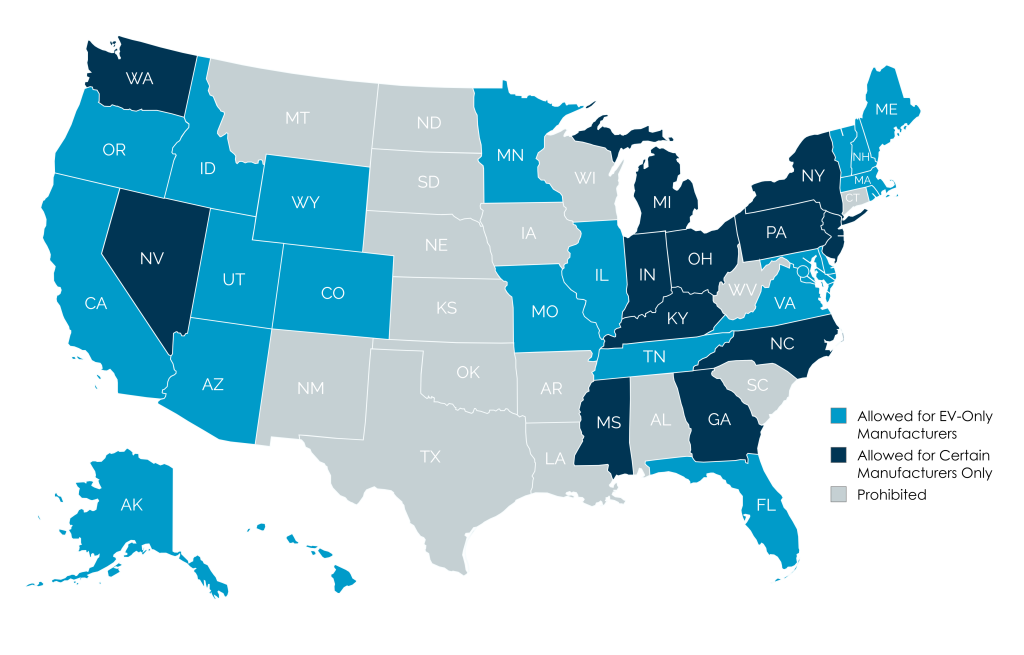

Currently, 21 states allow direct vehicle sales by manufacturers, many of them emphasizing electric vehicle growth and modernization.

According to the Electrification Coalition’s 2020 map, these 21 states (plus DC) allow unrestricted direct auto sales, while nearly 40% of states permit at least some form of direct electric vehicle sales — either for specific manufacturers or under certain conditions.

Credit: Electrification Coalition

The only critics who testified in opposition of the bill were South Carolina auto dealers, who argued that it would hurt existing car dealerships and undermine long-standing franchise investments.

Mark White, owner of the Steve White Auto Group in Greenville, testified that the quasi-Volkswagen affiliated line Scout, would be sold as a separate brand with no history of dealership partnerships, potentially undercutting the investments made by its existing Volkswagen dealer partners, including his own business.

White questioned the fairness of Scout Motors receiving $1.29 billion in economic incentives to build the plant while also seeking exemptions from South Carolina’s franchise laws. He said that those laws provide a secure framework for dealerships to invest in the future. But the bill would leave all existing franchised dealership agreements in place, including for all Volkswagen dealers. Only new automakers without existing franchised dealer agreements like Tesla, Rivian or Scout Motors would be able to sell directly to customers.

According to a report by the National Automobile Dealers’ Association, franchise dealers perform better in states that give consumers the freedom to choose from both options. In states that were open to at least one EV manufacturer, franchise dealerships saw their sales revenue increase nearly 80% between 2012 and 2021. During the same period, states closed to direct sales only saw a 61% increase in sales revenue. Dealership employment saw a similar trend, with open states seeing an almost 11% increase in employment, whereas closed states only had just over 6.5% increase in employment.

Where the Direct Sales Bill Now Stands

After hearing testimony, the subcommittee adjourned debate on the legislation, essentially killing it for the first year of the two-year session. The Consumer Freedom Act could be dead permanently for the 2025-26 session if the committee keeps it bottled up in 2026. South Carolina now finds itself at a crossroads between protecting franchised dealerships and adapting to a shifting, consumer-driven auto market.

Because the bill did not advance, the question remains unresolved: should consumers have the right to buy automobiles directly from manufacturers? Whether or not the Consumer Freedom Act gets revived next year or in a future legislative session may ultimately depend on how lawmakers balance the interests of franchise dealers with the growing demand for innovation and broader market access.

Palmetto Promise Institute finds that the S.C. Consumer Freedom Act is consistent with the principles of a free market, reducing regulatory overreach while empowering consumers with more options.