Time to junk the ESA? Not so fast, my friend.

Yesterday evening, the lame duck South Carolina Supreme Court surprised no one with the announcement that they weren’t interested in rehearing Eidson et al. v. South Carolina Department of Education et al., the legal proceeding also known as “the ESTF case” or the “the school choice case” (or, incorrectly, the “school voucher case”).

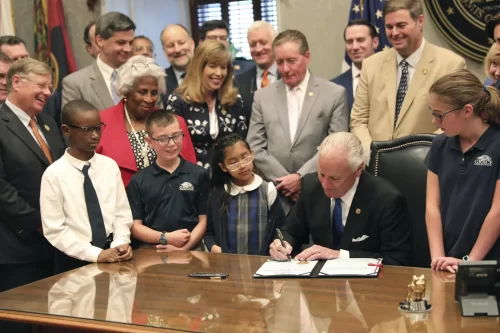

To some, this action from the high court is proof that the trust fund mechanism found in the Education Scholarship Trust Fund (ESTF) statute (seen above being signed into law in May 2023) is irredeemable, that after Adams v. McMaster (2020) and Eidson v. SCDE (2024), a trust fund-based school choice program is a permanent non-starter for South Carolina, and to think otherwise would be like refusing to learn from the second kick of a mule. Ipso facto, that means if we are to save school choice in the Palmetto State, we must run to the open arms of the funding mechanism known as the refundable tax credit.

Our reaction to this logic? In the immortal words of College Gameday’s Lee Corso, “not so fast, my friend.”

Let’s face it, the two Supreme Court decisions in question were legal holdings in name only. In actuality, they were pure politics. Though it is hard to decide which decision was worse, Eidson would probably win the prize, as it was a toxic elixir of lefty politics with a bizarre and inaccurate take on 1960s and 1970s South Carolina history.

At the risk of oversimplification, here are the key points that show why the ESTF mechanism is legal, remains popular with the legislature and the governor, and has a decent chance at being found constitutional.

- Governor John West, the South Carolina legislature, and the electorate of South Carolina worked together in 1972-73 to change the state constitution so that direct aid to students in private and religious schools, which was only indirect aid to the schools themselves, would be legal.

- Before the 1972-73 change, these types of programs—most famously a program for students in private and religious colleges— were found to be illegal under the old constitutional language and therefore failed to launch.

- Since 1972-73, with the constitutional change, these very programs flourished and are still with us today. A parent of a pre-K student attending a church kindergarten through First Steps or a parent of a private or religious college student funded through a Tuition Grant can tell you they are alive and well. These programs are at best indirect aid to the churches and the colleges, not direct, and 3,650 pre-K and 12,500 college students in the state use them every year.

- With the Education Scholarship Trust Fund (ESTF) program, the state creates a trust fund, which is a separate state account from the state general fund. Parents whose children are accepted into the program access those funds through a portal, and the parents spend the funds on an educational program of their choosing for their child. Private school tuition is an option but there are many other options for eligible educational expenses (such as public school interdistrict transfer fees, disability services, tutoring, curricula, and more). That’s clearly legal within the bounds of the 1972 Amendment (indirect) and virtually identical to First Steps and Tuition Grants. The funds aid the students, not the schools.

- Justice John Kittredge, who took over as Chief Justice on July 1, 2024, laid all this out beautifully in his dissent from the majority opinion in Eidson.

- Two of the three justices in the majority that struck down ESTF were former Democratic members of the SC General Assembly. Those same two justices have since retired from the bench.

- As our parent stories have shown to a heartbreaking degree, if ESTF program kids are to stay in their new schools, they need our help now. They should not be shuffled off to another program or forced to take on massive credit card debt to compensate for the loss of their scholarships.

It is our firm belief that either later this year or in January, if the South Carolina General Assembly were to revisit the Education Scholarship Trust Fund— and both make it universal and correct a few legal drafting issues—the program would be found constitutional soon after, with the trust fund mechanism still in place.

As for the various types of tax credit funding mechanisms, those are worth considering as well. Florida has nearly all of them. But reading the legal tea leaves clearly shows that it is entirely too early to junk the school choice program funding mechanism we have. ESTF’s prognosis is quite good, and if we stick with it, rather than starting over, we can help ESTF kids stay in their new schools without interruption.

The South Carolina General Assembly would be wise to come back to the Statehouse soon to address this issue for families hurt by the Court’s unjust ruling so that children may finish the school year with their promised scholarships. Desperate families all over the state are at their wit’s end, which these real life stories clearly show, They are looking to Columbia for help.