The NEA Sues South Carolina: Does Their Tillman Constitution Claim Have Merit?

Last week, the National Education Association (The NEA/The SCEA) and others announced that they had filed suit against the State Department of Education, State Education Superintendent Ellen Weaver, State Treasurer Curtis Loftis, and the State Treasurer’s Office.

Their target? The fledging Education Scholarship Account (ESA) program passed by the legislature in 2023 that would allow low and moderate income children to attend the education provider of their parents’ choice—whether public or private.

The ESA program, known in the South Carolina legislation as ESTF, Education Scholarship Trust Fund, is set to launch for the 2024-25 school year. In January, the application window will open for 5,000 scholarships for children from families whose income is less than 200% of the federal poverty measure. Additionally, to qualify, a child would have to be entering kindergarten or have previously attended a public school.

So, why the lawsuit? Why is the NEA, with a budget of $543 million, concerned with 5,000 economically challenged children out of 758,815 pupils attending state public schools?

Why the opposition to parents choosing the public or private education that fits their children best?

The why isn’t much of a mystery, so let’s set that aside for now and get to the how.

The tip of the spear for The NEA’s attack on education choice in the Palmetto State is a provision of the South Carolina constitution and 37 other state constitutions known by the term “Blaine Amendment” or “no aid amendment.” These amendments were passed around the country in the “Know Nothing” Era (the end of the 19th century) to prevent states from providing aid to Catholic educational institutions.

The Blaine Amendment issue is complicated, but to keep this treatise short, allow us to leave you with just two points to remember about South Carolina’s version of the Blaine Amendment: 1) the Amendment was born in bigotry in 1895 and 2) it was modified in 1972 to open up opportunity.

First, let’s look at 1895. It was in that year that former Governor and sitting U.S. Senator Benjamin Ryan “Pitchfork Ben” Tillman was the state Boss Hogg. With the goal of undoing the democratic reforms of the 1868 Constitution, he demanded (and got) a Constitutional Convention. The Convention was an opportunity for the racist theories of Tillman and his allies to find their way into the fundamental law of the state. Provisions that were designed to prevent African-Americans from voting are well-known because Tillman bragged about them in a vile speech on the floor of the U.S. Senate.

But the Blaine Amendment that was added at that time had a racial element as well. National nativist organizations, which sowed fear into white Anglo-Saxons about the rising tide of Irish and Italian [Catholic] immigration, put pressure on the South Carolina convention to ban public support for “sectarian” [Catholic] institutions. That effort dovetailed nicely with homegrown anger at South Carolina Roman Catholics for their longtime education work in the African-American community. (That animosity was alive and well in 1940, when a suspicious fire destroyed a Roman Catholic church and school built to help educate the black community of that city on the day before it was to be dedicated.)

The language of the South Carolina Blaine Amendment left no doubt about its intentions. Public schools being safely Protestant at that time, the ban on “church” and “sectarian” aid meant only one thing: a ban on direct or indirect aid to any Catholic institution. This is a source for the bogus doctrine of “separation of church and state.”

The original 1895 “no aid” [Blaine] amendment was long. It read:

The property or credit of the State of South Carolina, or of any County, city, town, township, school district, or other subdivision of the said State, or any public money, from whatever source derived, shall not, by gift, donation, loan, contract, appropriation, or otherwise, be used, directly or indirectly, in aid or maintenance of any college, school, hospital, orphan house, or other institution, society or organization, of whatever kind, which is wholly or in part under the direction or control of any church or of any religious or sectarian denomination, society or organization.

***

Fast forward to 1972. In South Carolina government, the 1970s was a time for pulling back from some of the worst excesses of the Tillman Constitution. A committee composed of legislators and scholars had recommended the changes in the 1960s, but it was in the 1970s that the most significant changes made their way to the ballot for voter approval.

The push to amend the state Blaine Amendment in that year came from an unlikely source: private religious colleges. The smaller denominational colleges were struggling financially and efforts to aid them (and prevent their students from being dumped onto the state colleges if they closed) had been stymied by the 1895 version of Blaine quoted above. So, a new text was proposed that simplified that Amendment and removed the word “indirect.” The voters approved the change in 1972 and the legislature ratified it in 1973:

No money shall be paid from public funds nor shall the credit of the State or any of its political subdivisions be used for the direct benefit of any religious or other private educational institution.

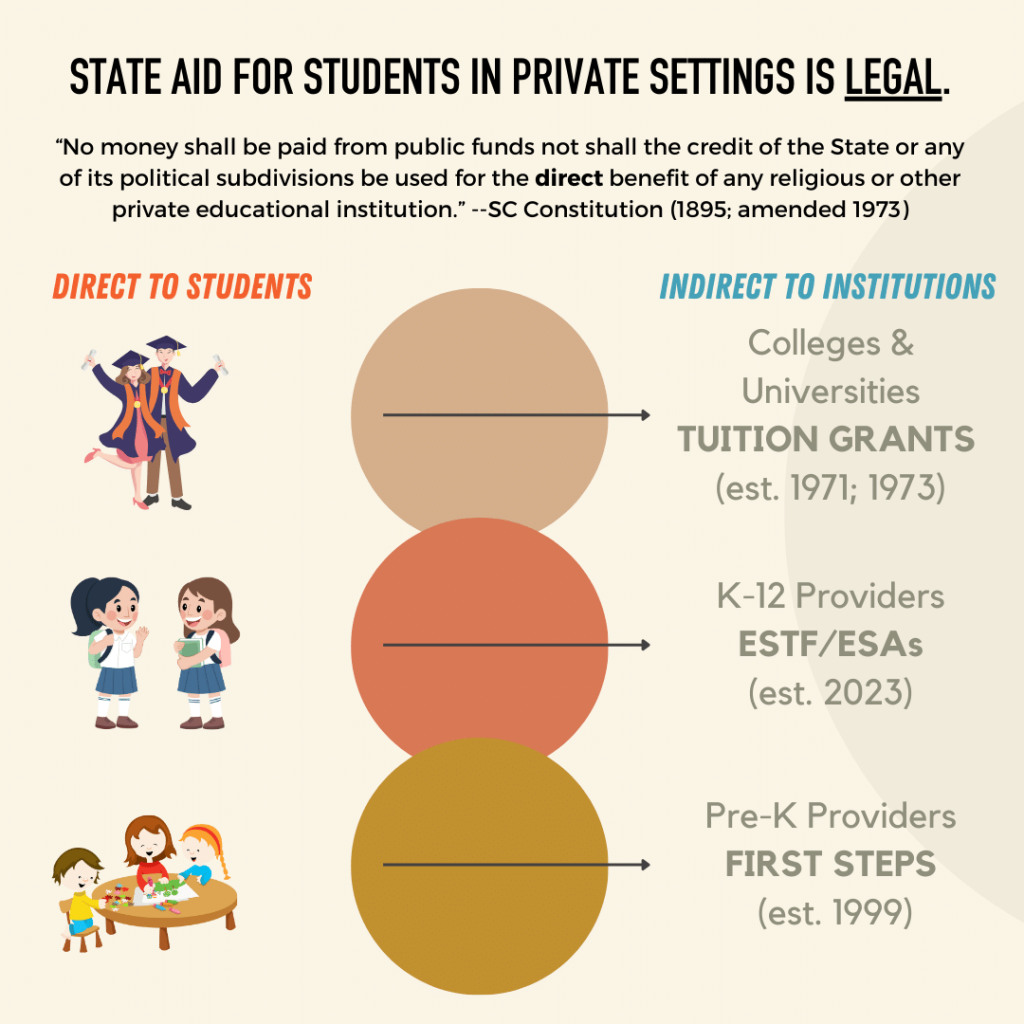

- Shortly thereafter, with the Constitution “fixed,” the Tuition Grants program, a state-funded program for students attending religious or other private colleges, became viable. For 2021-22, the Tuition Grants Commission received state appropriations of $53,488,624. Tuition Grants represent indirect support for private and religious institutions but direct aid to the students. (This is in addition to other scholarships that are offered to public and private university students like LIFE and HOPE.)

- On the other end of the age spectrum, in 1999 South Carolina First Steps to School Readiness was established. This state-funded program supports both public and private preschools.

- As the graphic (above) illustrates, the Education Scholarship Trust Fund (ESTF) merely fills in the gap between pre-school and higher education. All represent constitutional direct aid to students which is indirect aid to institutions.

So, did the framers of the constitutional revision that passed verbatim in 1972 and was ratified by the General Assembly in 1973 envision support for students in private colleges only, or were other levels of education in play?

For a little historical perspective, and a needed dose of original intent, here is what they wrote about their recommended amendment:

The Committee fully recognized the tremendous number of South Carolinians being educated at private and religious schools in this State and that the educational costs to the State would sharply increase if these programs ceased. From the standpoint of the State and the independence of the private institutions, the Committee feels that public funds should not be granted outrightly to such institutions. Yet, the Committee sees that in the future there may be substantial reasons to aid the students in such institutions as well as state colleges. Therefore the Committee proposes a prohibition on direct grants only and the deletion of the word “indirectly” currently listed in Section 9. By removing the word “indirectly,” the General Assembly could establish a program to aid students and perhaps contract with religious and private institutions for certain types of training and programs.

Clearly, the framers of the 1972-1973 revision saw a future need for supporting students in private K-12 programs, not just colleges and universities!

So, to us, The NEA’s suit against South Carolina has no merit. At least if one believes in original intent…and the legality of higher ed tuition grants and First Steps 4K.