Assessing Schools: Ambiguity Isn’t Accountability

Dr. Oran Smith

I’ll never forget my first day of Sixth Grade. I had left elementary life behind and in my mind was grown up—I was a middle schooler after all. But for the first time, a change in grade also meant a change in school. And my what a difference in school. The middle school campus I attended was a part of the now infamous “Piedmont Schools Project,” a 1970s era scheme that ranks with New Math and New Coke for ideas that were not only really bad, but avoidable and expensive.

Of all the purported innovations of PSP, two were particularly bizarre: no walls and no grades. Rather than each of the sixth grade subjects—math, English, social studies, science—having its own classroom integrity, all classes met simultaneously in a “cluster” without walls in between. Five classes meeting, five teachers trying to be heard, five teachers trying to limit distractions…in one big room. It was a “cluster” alright. I can’t tell you how many hours I spent with my head on my desk while our poor teachers roamed around struggling to restore order.

Then there was the grading. The educational theories of the 1970s insisted that self-esteem be prized above all, so the system was purposely vague. A, B, C, D and F were gone, replaced by: ✔️+, ✔️ and ✔️-. I’ll never forget coming home with that report card. I assured my parents I was doing well in all subjects. After all, all of my grades included a check! They were (forgive me) non-plussed. Those “marks,” as they called them in the old idiom, meant nothing.

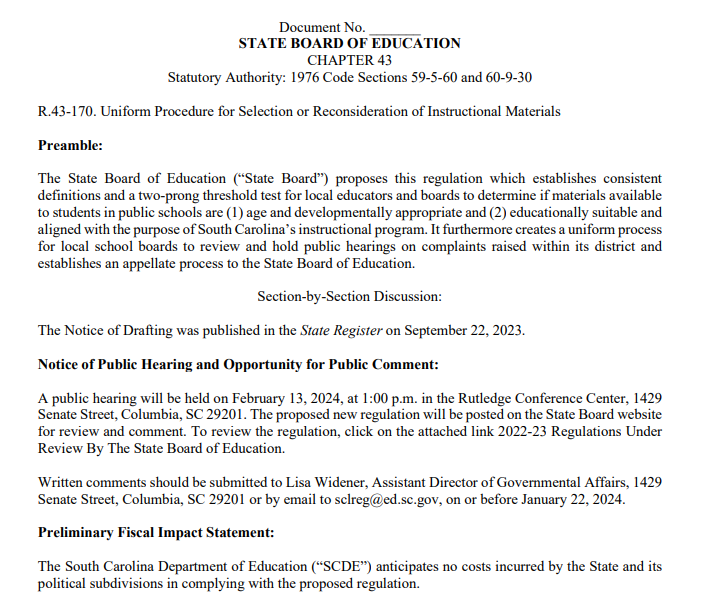

Flash forward nearly forty years in education policy to last October (2015) when President Obama signed the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA). ESSA is the successor to No Child Left Behind, Race to the Top, and a number of other federal education reform laws dating back to, well, the days of the Piedmont Schools Project.

ESSA has lots of problems. But, thanks to folks like US Senator Lamar Alexander (R-TN), under the new law, every state must produce a report card for each school, school district and the state system as a whole. It is mostly up to the state to determine the components that make up the report card, but in order to receive funds from the federal treasury, each state must adopt some type of dashboard that is designed not for educators, but for the public.

South Carolina is in the throes right now of crafting our report cards.

Last week, I testified before our Education Oversight Committee of behalf of Palmetto Promise Institute that South Carolina should adopt a system that “boldly rewards excellence with transparency.” In our view, that means one thing: an A, B, C, D, F grade for each school, school district and the state as a whole.

This week, it was the SC Association of School Administrators turn to appear before EOC. Their recommendation could not be further from ours. The SCASA plan called for “public transparency on key performance indicators” but opacity seemed to be the true goal.

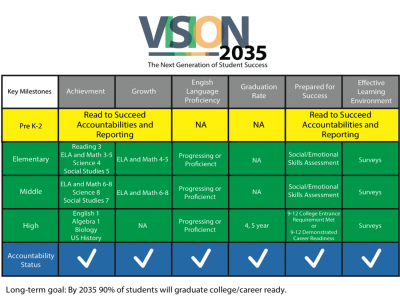

Following the outlines of ESSA, the SCASA framework called for schools to be graded on achievement, growth, English language proficiency, graduation rates, prepared for success and effective learning environment. (It appears that spelling may also be an issue we need to address, notably the word “achievement” in the first column, but I quibble.)

In looking at this dashboard, three concerns are paramount: there is no weighting of each indicator, there is no single grade for each school, and the grade or “accountability status” for each of the indicators is that great contribution of 1970s education schemes…a check mark.

- No weights. As we have said before, the weighting is absolutely key to a proper accountability system. Too much emphasis on achievement and kids get left behind, too much emphasis on growth and achievement will plateau or decline. Too much emphasis on softer parameters like “effective learning environment” and we have a beauty contest, not a reliable guide to a child’s school.

- No single grade. Without a single grade, parents and communities are in the dark. We have been through the horrors of “not met” and “challenge” ratings in South Carolina before. This is not transparency. Ambitious educators will emphasize the benchmark that looks good and ignore the rest.

To provide a layman’s example, what if rather than a final score, ESPN chose to start reporting random six (6) random statistics for college football games online—first downs, net yards rushing, net yards passing, total yards, time of possession and turnovers. A Clemson fan logging in from Australia would have thought the Tigers had lost the Louisville game. Or the Gamecock fan in China reading only cherry-picked stats would have been left with the mistaken impression that Carolina had lost to Vanderbilt. A community can rally around a grade or a score. Cherry-picked statistics mean nothing and rally no one.

- The dreaded check mark. We would argue that when the Federal ESSA statute clearly says that states must establish “long term goals which shall include measurements of interim progress toward meeting such goals” and that states should “[a]nnually measure, for all students the following indicators…” that the Feds are serious about a legitimate measurement. To statisticians, in order of strength, there are three scales of measurement: nominal, ordinal and interval. An example of a nominal scales would be Yes/No or a check or no check. Ordinal would suggest an order from say, good to bad, but not much else. Interval data, which we should always strive for in measurement in public policy, is like a thermometer, or like A-F. There are specific intervals of equal size between each gradation. A check or no check is virtually meaningless and we believe not consistent with the letter of the spirit of the federal ESSA law.

We will have more to say about accountability as the Education Oversight Committee continues to deal with state report cards, but we can tell you two things emphatically—if the SCASA system were adopted, we would have ambiguity in assessment, and ambiguity is not accountability to parents or the public.

Secondly, we can already project that actual legislation may be required to insure that South Carolina parents get the information they need and deserve. But what a bold stroke for true accountability to parents it would be if our elected representatives would stand with us for an A-F system!

If legislation is needed, we hope you will join with us. Stay tuned!