Pending Lawsuit Could Unleash American Energy Innovation and Lower Your Power Bills

Does the federal Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) have the power to regulate emerging nuclear technologies like Small Modular Reactors (SMRs)?

That is the question being posed in a new lawsuit brought against the NRC by several nuclear technology companies in cooperation with the states of Texas, Utah, Louisiana, and Florida, as well as the Arizona Legislature.

What’s in play here and how could it matter for our power bills and energy capacity here in South Carolina? Let’s take a look.

Background

To understand the lawsuit, we’ve got to take a dive into the history of the Nuclear Regulatory Commission. Congress created the Nuclear Regulatory Commission in 1974, at the height of the Cold War and during an increasing interest in nuclear power here in the United States. Its predecessor, the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC), was created in 1946 and reconstituted in 1954. The AEC specifically focused on both encouraging commercial nuclear power and regulating the industry to ensure public safety.

With increasing concerns about radiation exposure and environmental protections, the AEC was abolished in 1974, and its responsibilities were split between the Energy Research and Development Administration (later folded into the Department of Energy) and the Nuclear Regulatory Commission. The ERDA took on the work of research, development, and promotion of nuclear energy, while the NRC became an independent agency to regulate civilian nuclear power plants and materials. The split aimed to separate the researchers from the regulators and ensure that the United States could avoid dangerous nuclear accidents.

Much of the language used to describe the responsibilities of the AEC remains in the code of laws and was simply transferred to the NRC. Notably, the law establishes the AEC (and then the NRC’s) licensing power to only those nuclear reactors using “special nuclear material in such quantity as to be of significance to the common defense and security, or in such manner as to affect the health and safety of the public.”

That passage is the crux of the argument being made in State of Texas v. U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission, which was filed December 30, 2024.

The Argument for Deregulation

As new nuclear technology has developed, the NRC has been regulating microreactors and SMRs in the same way it has regulated traditional large-scale nuclear facilities. That is an extremely arduous permitting process that can take years, as it involves public hearings, safety inspections, environmental impact studies, NRC review of all construction plans, and frequent audits, before a license can be issued. And in the meantime, energy demand in the United States (and here in South Carolina) only continues to grow.

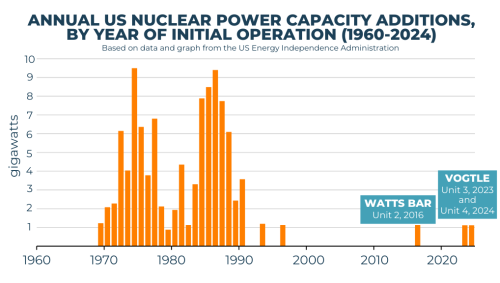

As you can see from the chart below, the approval and construction of new nuclear facilities in the United States have all but halted in the twenty-first century.

A complaint filed by the plaintiffs in the aforementioned lawsuit argues that “building a new commercial reactor of any size in the United States has become virtually impossible—indeed, only three new commercial reactors have been built in the United States in the last 28 years…The root cause is not lack of demand or technology—but rather the NRC, which so restrictively regulates new nuclear reactor construction that it rarely happens at all.”

This is where SMRs and other emerging technology come in. According to the plaintiffs, overregulation is stifling innovation in this sector in the name of public safety, because small reactors do not contain enough nuclear material to be dangerous. Last Energy, one of the lead plaintiffs, develops 20-megawatt SMRs that use minimal uranium. But, as stated in their filing, the NRC “imposes complicated, costly, and time-intensive requirements that even the smallest and safest SMRs and microreactors—down to those not strong enough to power an LED lightbulb—must satisfy” in order to be properly licensed.

The plaintiffs argue that this burdensome regulation was never Congress’ intent for the NRC, and that the Commission should require licenses only for larger reactors that process sufficient nuclear material to present a risk for security and public safety. They also raise the possibility that the states should regulate tiny reactors. The NRC refutes this, defends their regulatory authority, and argues that the complaint is inconsistent with the 2024 ADVANCE Act which directed NRC to license and regulate microreactors.

Why it Matters for You

State of Texas v. U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission is still pending, and currently, the NRC and plaintiffs are “in discussion” to pursue “a mutually agreeable resolution that could avoid or limit further litigation in this case,” in light of President Trump’s May 2025 executive orders promoting new sources of nuclear energy production in the United States. One executive order in particular aims to essentially “rubber stamp” approvals for reactors tested and found safe by the Department of Defense or Department of Energy.

If the NRC chooses to implement President Trump’s energy agenda, State of Texas v. U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission could be dropped or settled. But if the NRC continues to slow walk approvals, the plaintiffs likely will continue seeking a resolution in court.

These complicated legal and regulatory battles have real impacts on you and your wallet. It’s basic supply and demand—your energy bills get higher the scarcer energy supply becomes. If we embrace energy abundance and American-generated power, the energy supply will grow to meet demand, and prices will ultimately fall. This is essential as demand will only increase with the expansion of advanced computing.

It is also worth noting that in the bizarre world of energy finance, monopoly utilities essentially bill their customers in the rate base for the cost of their generation assets. SMRs will cost residential, commercial, and industrial customers less because SMRs are cheaper to develop than traditional large scale nuclear facilities. Expansion of Georgia’s new Vogtle Plant carried a price tag of $36.8 billion and took a decade to complete. V.C. Summer II and III in South Carolina was never completed and cost $9 billion.

Then again, there are other SMR developers outside the world of Investor-Owned Utilities (IOUs). Tech companies have expressed interest in building their own SMRs to supply their own data center needs, relieving pressure on the grid but possibly never connecting to it.

The United States should make it as easy as possible for new energy generation to go online. With proper processes in place, SMRs and microreactors would not pose the threat to public safety that traditional large scale nuclear facilities do, and the American people could rest assured that streamlined approvals for these facilities would not compromise citizen safety. New generation would mean lower energy bills, faster computing, and a new dawn of American technological innovation.

Note: David A. Wright, a former South Carolina state legislator and Public Service Commissioner was appointed Chairman of the NRC by President Donald Trump in July. Chairman Wright previously served on the NRC from May 2018 to June 2025.